Beware of the man who won’t be bothered with details. — William Feather, Sr.

Goal

In this essay I want to shed some light on the details when dealing with large datasets (read: arrays), while working with Python and numerical code when datasets become increasingly large (or local memory being not enough or the overall computation being too slow using Python’s standard libraries).

Motivation

Recently Jonas Bhend from the always impressing MeteoSwiss and me had an interesting discussion where we tangentially covered large arrays and how to deal with them in Python. This is of particular interest these days as we have seen a lot of efforts to ‘compress’ and distribute large arrays to some degree in relation to Large Language Models (LLMs). Starting with the leak of Llama by Facebook and ChatGPT – whose theoretical and architectural details I have written about a few years ago – a flurry of innovation unravelled in the FOSS scene.

Considering very large arrays and distributed computing, the last time I was looking into speeding up numerical code close to the metal was the optimization of a fix-point iterator for a large equation system using Fortran and OpenMPI.

Today we will inspect what lies under Python’s hood. And how several shortcomings of Python are circumvented. 🧐

Introduction

The need to handle large datasets and do fast numerical computation on them starts already on a single machine. On a single machine we usually have a dedicated graphics card with its dedicated cache and own RAM and additionally the computer’s RAM.

Also, in the boundary of Moore’s law we deal with multiple cores these days. Thus, have an impressive amount of hardware caches at our disposal.

Given the problem that we have a large dataset and want to compute using Python: How to approach this with the hardware in mind and knowing that Python is an interpreted language requiring a virtual machine in its reference implementation running in a single thread?

(Large) Datasets/Arrays

Python itself implements arrays as lists or nested lists, which are implemented as a dynamic array. While this makes arrays very versatile and flexible, it is also slow as growth and shrinkage implies many reallocations.

NumPy - An Almost 30 Years Old Package

In practice NumPy is the tool of choice for arrays in Python, implementing them in C. And it does it already for almost 30 years, as Numpy was released in 1995 called ‘Numeric’ at its time. It is interesting to note that the array implemention stood the test of time enabling the compatibility with BLAS or LAPACK towards which Numeric was developed. Numeric/Numpy implements arrays as contiguous chunks of memory. Besides the size needed to be allocated, two other pieces of information are crucial: The stride, which is the amount of bytes to be skipped to the next element in a dimension. As already implied, we are dealing with C-type pointers all the way down, however, the datatypes are wrapped into an increasing amount of Python for interoperability, indexing, broadcasting or looping (over strides) to ease numerical computations. At the latter point good old Fortran is still part of the show.

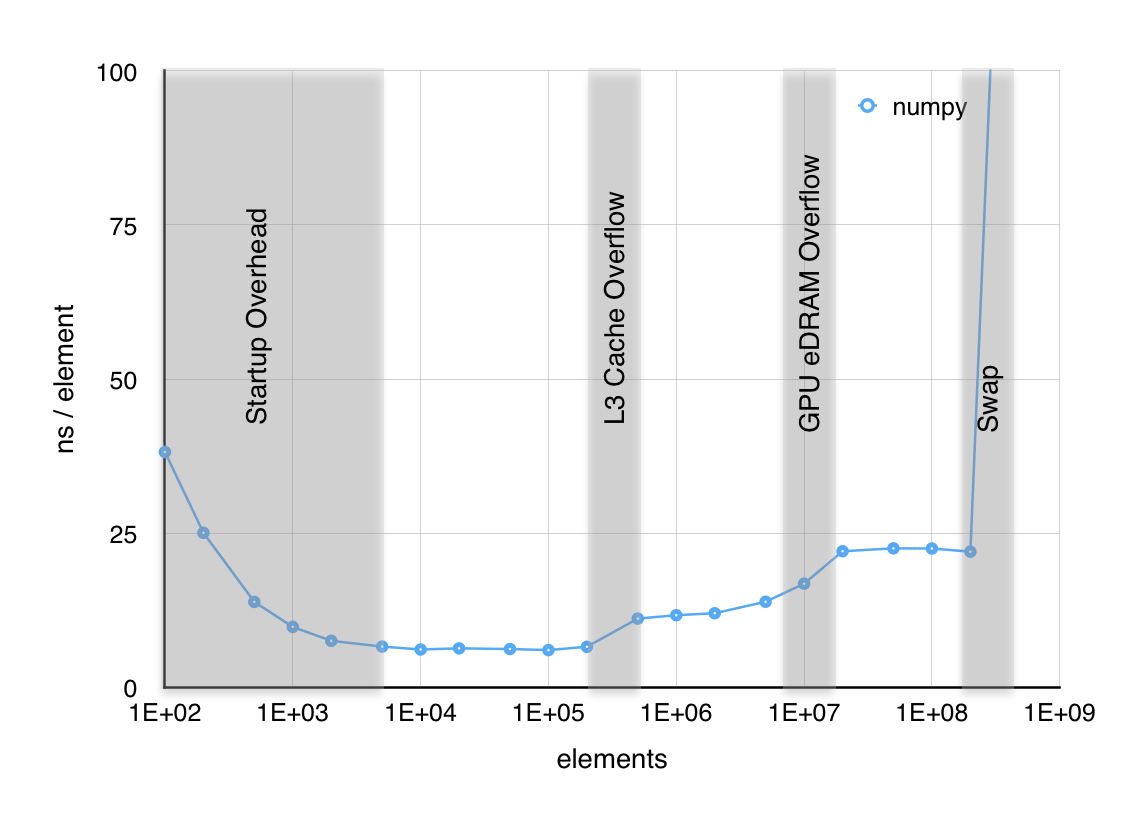

Yet, as shown by bitsofbits the time (ns) per element evaluation in large numerical expressions hits some natural boundaries:

And we did not see anything vectorized, parallel nor distributed yet. ☺️

NumExpr - Speed up

Let’s start with vectorization. NumExpr uses NumPy arrays, however, optimizes the evaluation of an expression using a VM written entirely in C being multi-threaded for ideal execution in the right type of memory taking size, stride, dimension and the specific data type into account. Chunking together with the VM doing JIT-compilation allows speed-ups up to 20x (and very rarely in case of small arrays or specific data-types slow downs). Besides SIMD vectorization NumExpr keeps the array in a platform adapted good state by reordering it as good as possible for the given operation.

As already mentioned, depending on the data-type this might backfire, so benchmarking is always a good idea.

Alright. We sped up our calculations compared to Python’s native lists by two to three orders of magnitude by now. So, what to do if a dataset is larger than the memory we have? A so-called beyond memory dataset.

Dask (and DistArray) - The Whole Package

Dask is somewhat the successor of DistArray similar to NumPy being the successor of Numeric. DistArray was developed with High-Performance Computing (read: distributed computing) in mind.

Dask incorporates NumPy arrays in small(er) chunks in a so-called dask array:

A given NumPy array is cut into smaller NumPy arrays using blocked algorithms which take into account the hardware at hand.

This design allows a set of interesting possibilities:

- We can use beyond memory datasets (!).

- That is, datasets which are larger than the given memory.

- Even doing efficient computation on it using blocked algorithms.

- Local parallelization,

- and global parallelization using a cluster.

And all of this in a familiar NumPy-like API. So far, basic arithmetic and scalar operations including some linear algebra are supported. However, similar like NumPy does, dask relies on BLAS, LINPACK etc. to cover np.linalg explicitly.

The ultimate benefit becomes visible in the integration of the dask array type in the ecosystem consisting of

- ‘Collections’: which incorporate our beloved NumPy arrays.

- The ‘Task Graph’: somewhat of an abstract syntax tree for our numerical evaluation.

- ‘Schedulers’: executing the graph created above,

- locally: using multiple threads, processes and whatever the hardware provides,

- distributed: using a set of computers, generally referred to as ‘cluster’.

Which enables multiple orders of speed-up for our numerical evaluations.

Conclusion

One could conclude with: Why not just use dask as it covers everything with fantastic speed-ups?

Well, the answer is: Yes. However, there are many use cases, where it is simply overkill and the added complexity is not worth the hassle.

My recommendation from today would be:

- Single-machine & Speedup needed: Start with NumExpr if need to optimize specific mathematical expressions on arrays exists.

- Beyond-memory and Out-of-core: Use

daskif hitting limits of your machine due to dataset size beating memory size. It’ll be easier if you want to parallelize computations later on to distribute.